Architecture

In the reign of Louis XVI, the fermiers généraux in charge of collecting taxes suggested to the king that he build a wall around Paris that would be 24 kilometers long and feature 55 entry points to allow levying taxes on merchandise.

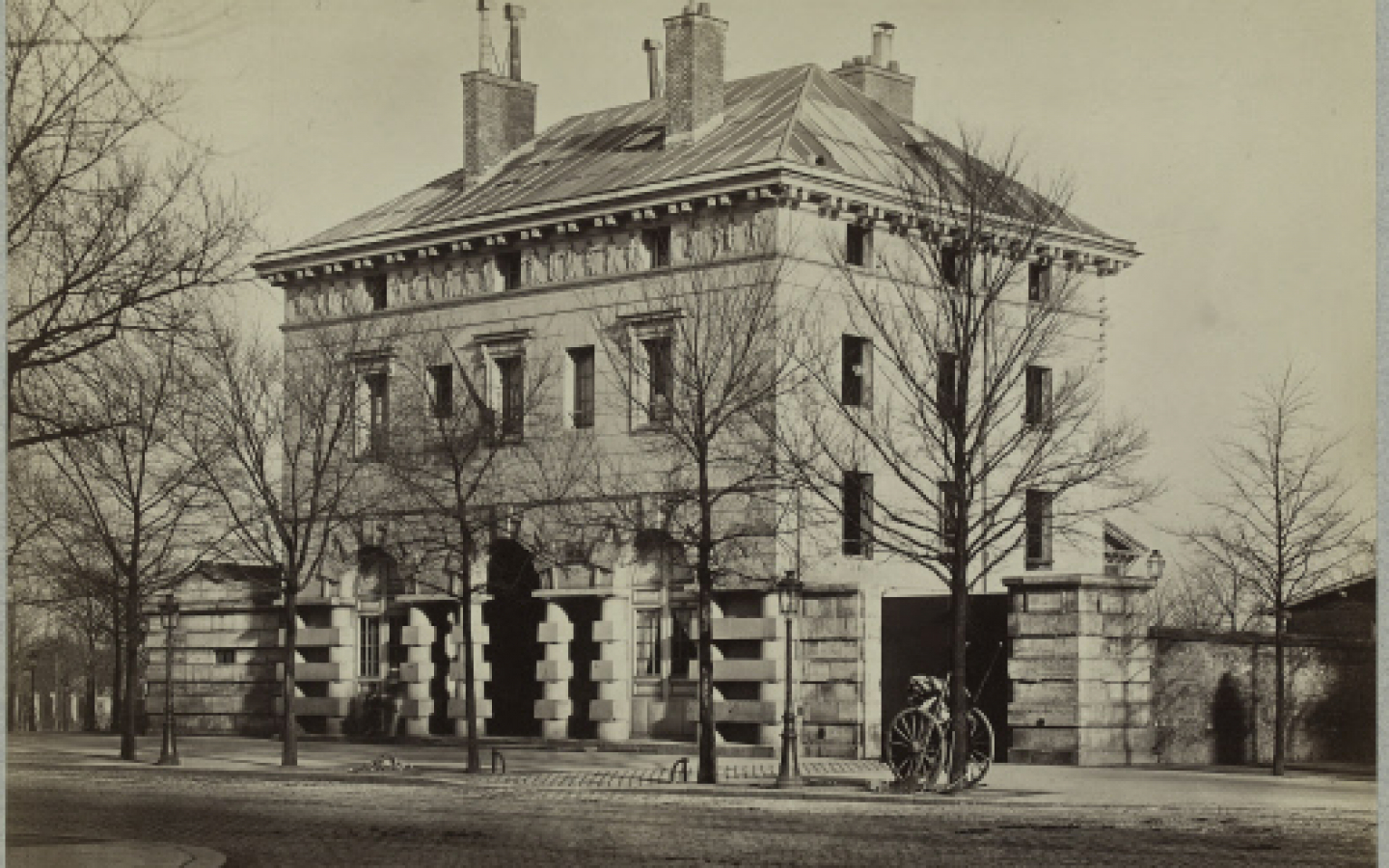

This was the most ambitious architectural and urban project of the Ancien Régime. Architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1743-1794) drew the project layout and elevations. For this barrier, the so-called “Gate of Hell”, he designed in 1785 two symmetrical rectangular pavilions that were located facing each other on both sides of the Route d’Orléans. The architect based his design on the propylaea of Ancient Greece, which were monumental gateways or vestibules placed at the entrance to a sanctuary. This impressive urban landmark recalled the power of the State to everyone who crossed the barrier and paid the entrance fee.

The two pavilions were built on four levels: ground floor, mezzanine, first floor and attic. On the main façade along the Route d’Orléans, a central flight of stairs led to a porch with three arcades on baseless Tuscan columns that alternated cylindrical, plain and cubic drums. These columns were prolonged in the protruding bosses on the ground floor. The central arcade forms a Venetian window (a central bay surmounted by a semi-circular arch and two side arches surmounted by a lintel). The only sculpted frieze, which is the work of Jean-Guillaume Moitte (1746-1810), is elegantly decorated with women dressed in the Antique style and holding medallions with the coats of arms of cities tied to the Barrière d’Enfer. The roof was in slate.

Symbols of royal power and unjust taxes, the barriers were the first targets of the revolutionary uprisings in July 1789. The Barrière d’Enfer was pillaged and burned on July 13. A report dated January 1790 notes that the Barrière d’Enfer, which was given the new name of Barrière Égalité (“Equality Gate”), had been repaired and housed the employees and renewed activity of the octroi. Dating from 1790-1791, these plans are conserved in the Historical Library of the City of Paris.

Taxes at the entrance to cities were suppressed in May 1791 and re-established in October 1798. There were successive transformations. The grillwork that barred the Route d’Orléans was modified, and the pavilions were reassigned. In the 1820s, the east building was converted into a barracks to house detachments of the municipal guard and the departmental police force. Employees of the octroi no longer occupied the west pavilion.

In the 1840s, the slate roof of the buildings was replaced with zinc.

In 1860, Paris grew by annexing the surrounding suburbs and municipalities. The octroi was moved to the entrance of the Thiers fortifications, built between 1841 and 1844. The perimeter wall by Ledoux was quickly demolished in the year 1860 to create a circular boulevard.

In 1867, the City of Paris installed its Department of Public Roads (which was later completed with a materials testing laboratory) and the Department of Quarry Inspection in the west pavilion. The east pavilion was occupied by the Paris guard until 1888, when it was replaced by the Quarry Service. A square was created in 1887.

Following the mobilization of the Commission du Vieux-Paris in favor of preserving the two pavilions, the former Barrière d’Enfer and the other barriers that were still standing (the rotundas of La Vilette and Parc

Monceau; the former Barrière du Trône) were listed as historical monuments by the decree dated April 13, 1907

Extracts from the historical and heritage study dated January 2016; Artene Architecture; Christophe Batard, Head Architect for Historical Monuments in charge of restoration